With the spread of Christianity and the collapse of the Roman Empire, the fashion for wearing head wreaths and diadems, probably considered ostentatious and deeply charged with pagan connotation, gradually disappeared. Crowns remained the symbol of power worn by royalty (see image 1), but we have to wait until the Middle Ages to see the return of tiaras in the shape of garlands of floral motifs, chaplets or bandeau worn around the head, frontlets and circlets of leaves, roses or trefoils worn as symbols of wealth and status.

The enduring appeal of the tiara | Part II - Developments in design to the Napoleonic period

In this second part of our survey we cover the period from the fall of the Roman Empire to the early 19th century.

Image 1: The Imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, 10th-11th century | Imperial Treasury at the Hofburg, Vienna, Austria

With its characteristic octagonal shape, the coronation crown was used until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Comprising eight hinged golden plates, the crown was probably made in Western Germany for the coronation of Otto I in 962.

Image 2: Statue of Gräfin Reglindis | Naumburg Cathedral, Saxon-Anhalt, Germany, mid 13th century

Reglindis (c. 989-1016) was the daughter of Polish King Bolesław I the Brave, and the Sorbian princess Emnilda; her husband Herrmann I (c. 980-1038) was Margrave of Meissen from 1009.

By the end of the 13th century, the coronal (circlet), consisting of a gold band surmounted by a series of fleurons variously encrusted with pearls and precious stones, had become the badge of rank proper for a king and princes, noblemen and noblewomen, knights and esquires and their wives and daughters (see image 2). Coronals were certainly worn at court and at festivals, both solemn and light-hearted but also on more ordinary occasions by royal and princely ladies. A coronal was amongst the wedding gifts a bride might expect from her father or bridegroom, a gift she would wear on her wedding day.

Image 3, Left: Piero del Pollaiuolo (1443-1496), Portrait of a Woman, tempera on wood, Florence c. 1480 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Piero del Pollaiuolo along with his brother Antonio, who had originally trained as a goldsmith, were responsible for some of the most distinguished female portraits produced in Florence in the third quarter of the 15th century.

Image 4, Right: Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), Idealised Portrait of a Lady, (Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as a Nymph), mixed technique on poplar, Florence c. 1480 | Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Simonetta Vespucci (c. 1453-1476), known as la bella Simonetta, was an Italian noblewoman from Genoa. Aged sixteen she married Marco Vespucci at the palazzo in Via Larga, Florence, and she soon was noticed at the Florentine court. At a jousting tournament held in 1475, Giuliano de’Medici entered the lists with a banner featuring the image of Simonetta as a helmeted Pallas Athene, painted by Botticelli, with the inscription ‘La Sans Pareille’, or ‘The Unparalleled One’; Giuliano won the tournament and he nominated Simonetta as ‘The Queen of Beauty’, in a chivalrous gesture of courtly love.

Simonetta’s pendant positions her closely within the Medici circle, as it imitates a famous cameo from the family’s collection.

Tiaras disappeared again during the Renaissance when women chose to wear their hair elaborately dressed and pinned with gem-set ornaments or entwined with strands of pearls and band of stones, and later with gem encrusted aigrettes worn in combination with feathers (see images 3 and 4).

It was only in the last quarter of the 18th century that tiaras came back in the form of naturalistic sprays and wreath of flowers which soon morphed, under the influence of Neoclassicism, stimulated by archaeological discoveries in Pompeii and Herculaneum, into formal wreaths of laurel leaves and pediment-shaped diadems.

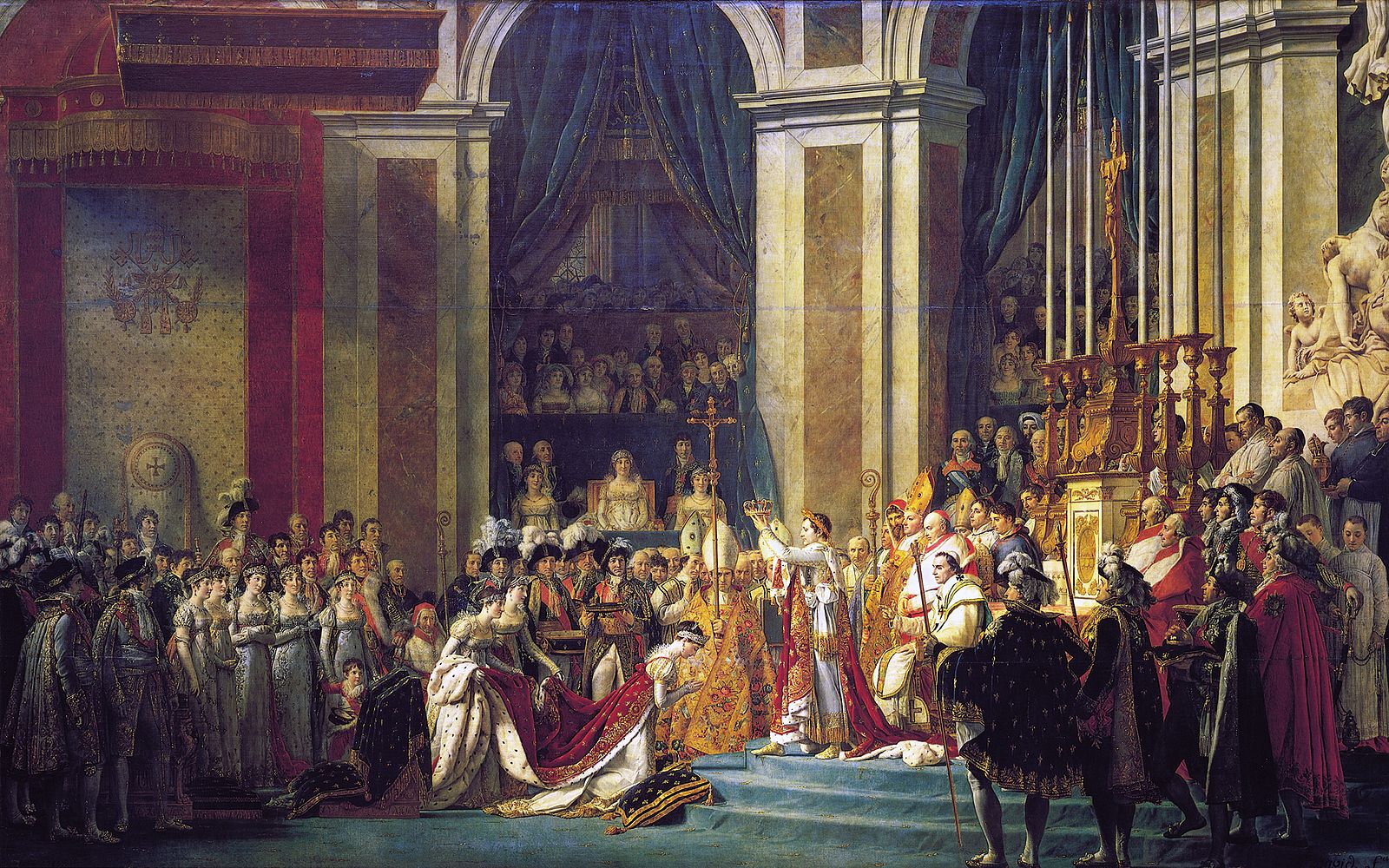

Image 5: Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), The Coronation of Napoleon, oil on canvas, 1805-07 | Louvre, Paris, France

The work was commissioned by Napoleon in late 1804, with final finishing touches completed in January 1808, and the painting was exhibited that year at the Salon annual painting exhibition.

Image 6: Napoleon, wearing a gold laurel leaf wreath, crowns Josephine

Image 7, Left: Josephine wearing a diamond pediment tiara

Image 8, Right: Napoleon’s sisters and sisters-in-law wearing jewelled tiaras of classical inspiration

Napoleon Bonaparte, who lacked the aristocratic background of his predecessors, sought to endorse his regime by association with Imperial Rome, and as a Roman Caesar, chose to be crowned with a formal gold wreath of laurel leaves. The painting Le Sacre de Napoléon by Jacques-Louis David captures the moment in Notre Dame on 2nd December 1804 when Napoleon, wearing a diamond laurel leaf tiara, crowns his wife Josephine who kneels in front of him wearing a diamond pediment tiara. Behind Josephine, Napoleon’s sisters are in attendance, clad in lavish jewels, their humble origins elevated to royalty by sumptuous tiaras of classical inspiration (see images 5, 6, 7 and 8).

Image 9: The Russian Nuptial Tiara, a spectacular diamond and pink diamond pediment tiara, Russian, 1800-1810 | Diamond Fund, Kremlin, Moscow, Russia

The centre of the tiara holds a 13 carat pink diamond from the Treasury of Paul I, (Tsar of Russia, 1796-1801), and it is likely that the tiara was created for Paul I’s wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna. The tiara can be seen in a photograph of the confiscated inventory of Romanov jewels and precious objects.

Image 10: Diamond tiara, formerly in the Thurn und Taxis collection. The rounded profile of this head ornament conforms to the fashions of the Imperial Court of France which were followed everywhere from the first decade of the 19th century. The jewel appears in the Tiara section of the 1750-1820 chapter of the online Understanding Jewellery.

Contemporary tiaras made all over Europe conform to this style which remained throughout the 1810s. They tend to be formal and symmetrical in design, decorated with motifs taken from classical antiquity: these include pediments, palmettes, laurel leaves, ears of wheat, volutes and Greek-key patterns (see images 9 and 10).

Image 11: Emerald and diamond diadem created by Maison Bapst, jeweller to the French Court, in 1819 for the Duchess of Angoulême, Princess Marie-Thérèse, the only surviving child of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. Made many years after the French Revolution with stones from the French Treasury, the centre emerald weighs nearly 16 carats and the tiara is set with 40 emeralds making the total weight 79.12 carats. The French state sold the tiara, along with the other French Crown jewels, in 1887 and it was acquired by the Louvre in 2006 in a later auction | Louvre, Paris, France

Set with pearls and diamonds, the most praised gems of the time, or embellished with rubies, emeralds and sapphires, these head ornaments, were designed to indicate the wealth and status, of the wearer (see image 11).

Image 12: Robert Lefèvre (1755-1830), Portrait of Maria Paola Bonaparte (1780-1825), wearing a hardstone cameo diadem and matching comb | National Museum of the Château de Malmaison, Paris, France

Napoleon, Maria Paola’s elder brother, made her the first sovereign Princess and Duchess of Guastalla, however, she soon sold the duchy to Parma, for six million francs, whilst retaining the title of Princess of Guastalla. Maria Paola died at the Palazzo Borghese, Rome, at the age of forty four.

Image 13: A gold and hardstone mosaic tiara, Italian, circa 1808, believed to have belonged to Napoleon’s sister Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples (1782-1839).

| The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection, on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Napoleon’s personal interest in the glyptic art prompted the production of equally stunning, if less expensive examples, set with engraved gems, cameos and intaglios carved in shell or hardstone with scenes taken from classical mythology and surrounded by borders of small pearls or gold filigree and enamel (see images 12 and 13). Worn by high-ranking women, tiaras were not confined to coronations and court or to formal occasions but were worn at weddings too.