Conceived as a simple wreath of branches and leaves, tiaras were, in their earliest form, mainly connected with religious and funerary ceremonies. Wreaths of natural leaves and flowers have been found in Egypt on the head and on the breasts of mummies of pharaohs dating from the XX and XXI dynasties (1200-945 BC) possibly confirming the general assumption that tiaras originated in the oriental world. However, these wreaths of natural leaves and flowers are predated by imposing gold head bands decorated with animal heads and stylised floral motifs from the Second Intermediate Period (1648–1540 BC) and from the New Kingdom (1479–1425 BC), see images 1 and 2.

The enduring appeal of the tiara | Part I - Early sightings: from Mesopotamia to Republican Rome

The form first seen in ancient civilisations has a long and distinguished history, and today the tiara is still the star at important state occasions and private events.

Here we present Part I in our four part survey.

Image 1: A gold headband with heads of gazelles and a stag between floral motifs, Egyptian, circa 1648-1540 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

During the late twelfth and then the thirteenth dynasty, late in the Middle Kingdom, people from western Asia established themselves among the Egyptian inhabitants of the eastern Nile Delta. A multicultural mix was thus created that culminated during Dynasty 15 in the rule of a line of kings now known as the Hyksos who dominated a good part of northern and middle Egypt. The northern "Hyksos" culture combined Egyptian and Near Eastern traditions and this diadem with animal heads alternating with flower motifs is a good example of the blend of artistic styles.

Image 2: A gold, cornelian and opaque turquoise glass diadem with two gazelle heads, Egyptian, New Kingdom, circa 1479-1425 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The gazelle heads are indicative of Near Eastern influences.

In Mesopotamia, excavations of the royal tombs at Ur – Southern Iraq – have brought to light a wealth of gold ornaments including stunning head ornaments designed as chains of gold leaf motifs alternating with hardstone beads dating from around 2600 BC, see image 3.

Image 3: A gold and lapis lazuli headdress, Sumerian, circa 2600-2500 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This chaplet of delicate gold leaves, cornelian and lapis lazuli beads adorned the forehead of one of the female attendants in the so-called King’s Grave in the cemetery of the city of Ur. As gold, lapis lazuli and cornelian are not found in Mesopotamia, their presence in burials in Ur is proof of a complex trade system that extended far beyond the valley between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

In ancient Greece, wreaths of leaves were beautifully crafted in gold to adorn the statues of gods and goddesses in shrines and temples: oak for Zeus, olive for Athena, myrtle for Venus, ivy for Dionysus, and laurel for Apollo. Gold wreaths were offered to divinities as ex voto, their weight carefully accounted for by the priests in the inventories of the temples. Wreaths of natural leaves, flowers and berries were worn during religious processions by priests and sacrificial victims, and in funeral rituals, gold wreathes were buried with the deceased to signify their victories in the battle of life.

Image 4: A gold stater, circa 323/2-315 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The head of Alexander the Great facing right is encircled by a wreath of laurel leaves, a statement of his power and status.

The ritual and religious dimension and the sacred character of the wreath of leaves probably promoted its diffusion in different contexts. The wreath – stephane – in Greek – became a symbol of political status and was awarded as a military honour, see image 4. Winners of musical contests and athletic games were crowned with wreaths and the habit of wearing a wreath purely as a form of adornment at banquets and weddings spread among the wealthy of both sexes and is amply testified to by literary sources and vase painting, see images 5 and 6.

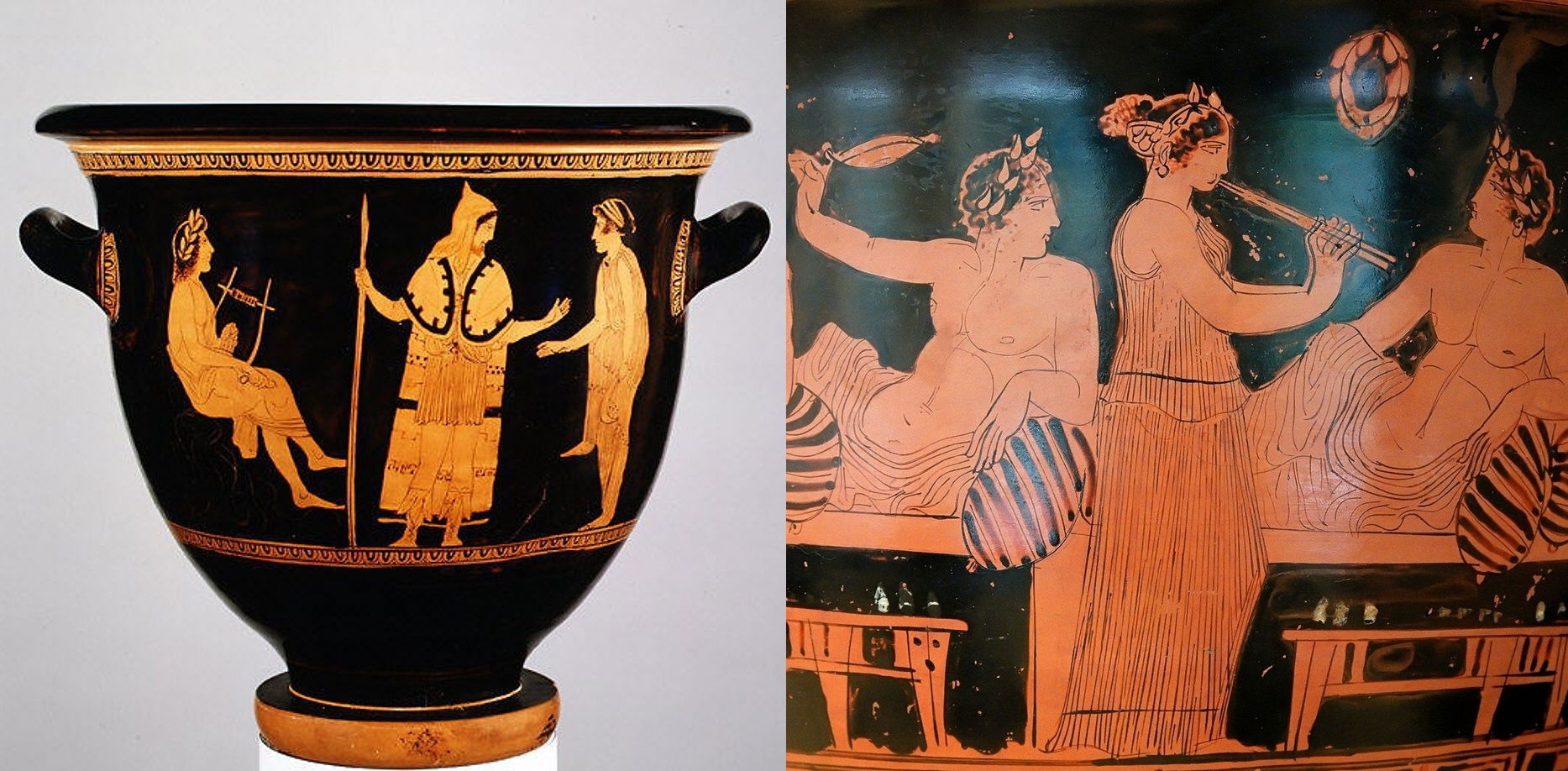

Image 5, Left: A terracotta bell-krater, Greek, circa 440 BC, attributed to the Painter of London | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The figure depicted on the left wearing a laurel leaf wreath and playing the lyre is Orpheus, the best known of the mythical musicians who learnt his great skills from Apollo

Image 6, Right: A terracotta bell-krater, Greek, circa 420 BC, Nikias Painter | © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España, Madrid

The scene depicting a banquet shows the habit of wearing a wreath purely as a form of adornment

Archaeological excavations in Southern Italy, Macedonia and Southern Russia, brought to light fabulous gold examples of tiaras made of olive, oak, laurel, myrtle leaves and at times interspersed with berries, flowers and insects, realistically rendered, see image 7.

Image 7: A gold ivy wreath, from Kastellorizo (Megisti), Greek, mid 4th century BC | George E Koronaios / National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Although impressive looking the vast majority of these wreaths are too flimsy to have been worn by the living, and must have been especially made for funerary use, to secure the maximum effect with the minimum outlay of precious metal.

Image 8, Top: A gold diadem, Greek, 4th century BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The thin gold sheet in the form of a pediment is decorated with motifs of palmettes in low relief. This type of diadem, made from thin gold sheets with impressed decoration, enjoyed long-lasting favour. Similar examples have been found in tombs that range in date from the 5th century BC to the Roman period

Image 9, Bottom: A gold diadem, Greek, 3rd century BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This elaborate example, probably from Southern Italy, consists of band of gold applied with fourteen floral motifs interspersed with gold beads. The petals of the rosettes are secured to the band by a gold sphere decorated with granulation.

The other form of head ornament worn in ancient Greece was the diadem (from ‘diadein’, to bind around) a gold band embossed or applied with rosettes or other floral motifs, see images 8 and 9. More elaborate examples consisted of a crossover of gold bands connected by a Herakles knot motif, see image 10. In Hellenistic times, these ornaments, often rising to a pediment at the centre, were invariably decorated with more elaborate figurative scenes inspired by Greek mythology, see image 11. Later, the word ‘diadem’ came to denote the purple band with a white decoration, worn by Persian kings around their high-peaked headdress. Interestingly, the name for this type of headdress was ‘tiara’ the word now widely used with minimal variations in many languages, to indicate a variety of head ornaments that embraces circlets, diadems, wreaths, and kokoshnick.

Image 10, Top: A gold cross-strap diadem, Greek, circa 300-250 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In this example found in a tomb in the island of Ithaka, the straps meet at the centre to form a Herakles knot embellished with rosette motifs and set with garnets.

Image 11, Bottom: A gold diadem, Greek, circa 330-300 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This gold pediment diadem is said to have come from a tomb in Madytos, on the European side of the Hellespont. The thin gold band is decorated in repoussé with a rich and intricate pattern of leaves and volutes. At the centre sit Dionysos, the god of wine, and his wife Ariadne, and at their sides, perched among the volutes, muses play musical instruments.

In Republican Rome, jewellery was for long under official disapproval. The Law of the Twelve Tables, in the 5th century BC, limited the amount of gold which which the dead could be buried, and in the 3rd Century BC the Lex Oppia stipulated that an ounce of gold was all the precious metal a Roman lady could wear. The situation changed in the late years of the Republic and by the time the Empire was inaugurated in 27 BC well born women had acquired a taste for wearing pearls, gold and gemstones in great abundance. The Romans adopted the gold wreath as the supreme indication of rank and honour for both men and women, see images 12 and 13.

Image 12, Left: Mummy portrait of a young woman, Egypt, Roman period, AD 90-120 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Note the gilt wreath encircling her head

Image 13, Right: Mummy portrait of a man, Egypt, Roman period, AD 140-170 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Roman imperial wreaths are often very different from the realistically rendered Hellenistic examples, they are made up of stylised gold leaves often attached in groups of three to a band of material, alternating with gold berries, see image 14.

Image 14: A gold funerary wreath of acorns and oak leaves, Roman, 1st–2nd century AD | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Egyptian mummy portraits of the Roman period often show the deceased wearing such wreaths. This is true for both men and women, as seen in the images above