The announcement last month of the discovery of what is claimed to be the third largest rough diamond ever to have been unearthed, raised a number of questions for me about the future of such massive stones – and reminded me of some of the polished gems to which they give birth.

Weighing in at no less than 1,098 carats this particular diamond was recovered by Debswana, a joint venture between the government and De Beers in Botswana. Of course, this is not the first gigantic diamond to be found in Botswana in recent years – many will remember for example the now famous Lesedi La Rona. The Lesedi was in fact very slightly larger than the stone announced last month. Weighing 1,109 carats meant that when it came up for sale at Sotheby’s in June 2016 it was possible to bill it as the largest rough diamond to surface in over 100 years – since in fact the discovery of the legendary Cullinan diamond in South Africa in 1905.

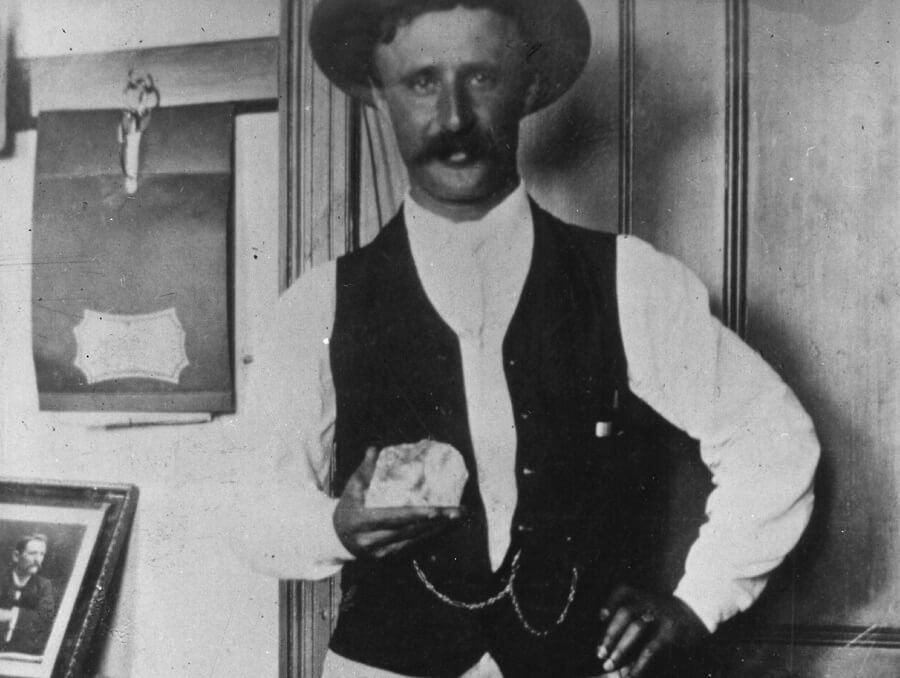

The Cullinan weighed a whopping 3,106 carats and was to be the origin of a number of the most famous diamonds in the Crown Jewels including the Great Star of Africa, which at 530.4 carats is still the largest top colour diamond in the world