I was passionate about archaeology, I loved antique history and graduated in classics. I just about knew that sapphires are blue and emeralds are green when I was offered a job at Sotheby’s in the jewellery department. It was that unexpected offer and my irrational decision to take up the challenge of a job I knew nothing about, that ignited in me the interest in jewellery that subsequently developed into a true passion. I had to learn quickly and I was very fortunate to have as my mentor, Peter Hinks, a true jewels’ historian who would spend hours inspecting and studying a jewel of low intrinsic value but of great relevance to the development of jewellery history because of its design or the type of manufacture. From Peter I learnt that there is so much more than gold and precious stones in a piece of jewellery.

Daniela shares her passion for antique and vintage jewels

As a child I was something of a tomboy, not particularly interested in fairy tales, princesses’ costumes, magic wands, jewels and tiaras. Jewellery was not my teenage passion either and I never thought of gemmology as a possible subject for my university studies.

One of many spectacular historic jewels from Jewels from The Princely Collection of Thurn und Taxis. A pearl and diamond tiara, created by Gabriel Lemonnier, commissioned by Napoleon III as a wedding gift for his bride, Eugénie de Montijo, in 1853. Featuring 212 pearls and nearly 2,000 diamonds set in foliage scrolls with upright pear-shaped pearls set in silver.

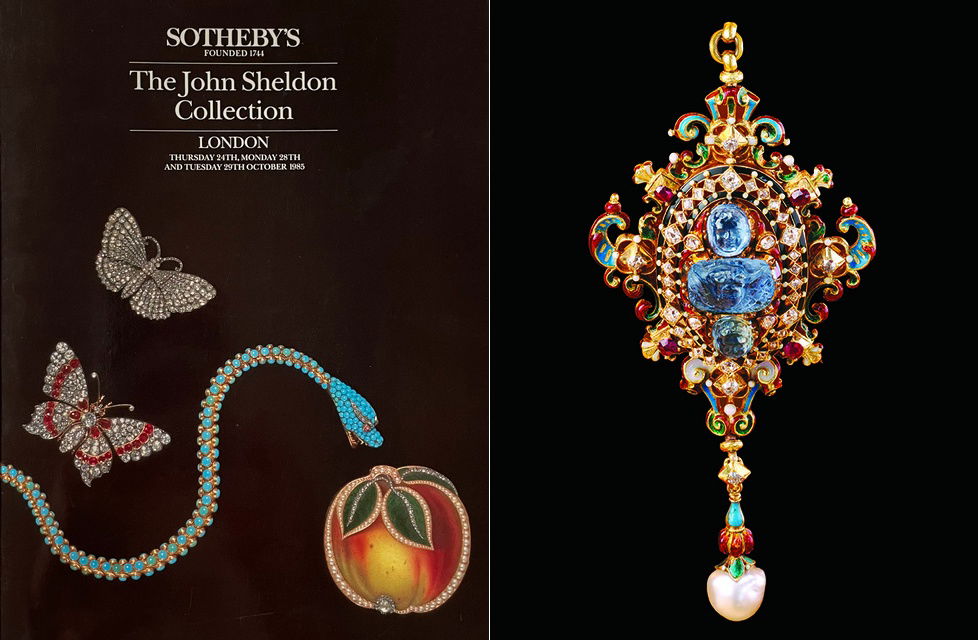

Left: the front cover of the auction catalogue for The John Sheldon Collection, held at Sotheby's London, October 1985 | Right: Enamel and gem-set pendant by Carlo Giuliano from the collection

My interest in history and archaeology encouraged me to delve deeper into past jewels: the origin of their design, their function, the dress fashion they were meant to complement, the artist who created them and the person who commissioned them. I gradually started to look at jewels with the eye of the art critic and examine them with the combined skills of the archaeologist, the historian and the gemmologist. As the art critic distinguishes the decorative object from the true masterpiece, my eye eventually was trained to detect quality in jewellery and distinguish merely glittering ornaments from the true exceptional creations. These I like to consider true miniature objets d’art. Jewels are intensely personal and more than any other possession they can tell so much about their owner and their time.

My first exposure to a truly spectacular and varied collection of jewellery was in 1985 when Sotheby’s London was entrusted with the sale of the jewels, silver and objects of vertu put together by the late John Sheldon of Bentley & Co., a well-known and distinguished member of the jewellery trade, a passionate connoisseur and lover of beauty. His personal jewellery collection spanned from 18th century foiled crystals bracelets to early 20th century butterfly brooches and included an important and spectacular group of revivalist jewels created by the Giuliano family. Examples of all different types of jewels and of the many jewellery techniques used in jewellery over two centuries were included in that collection: cataloguing it proved to be a fantastic learning process that gave me enormous pleasure. Always interested in the ‘look’ of the catalogue, I remember assembling the jewels for the cover of the catalogue, featuring at the front a gold and turquoise snake necklace and a snuff box in the shape of a peach – which I thought at the time could pass for an apple.

Onyx and diamond Panther bracelet, Cartier, Paris, 1952, Provenance: Collection of the Duchess of Windsor.

The articulated body is designed to encircle the wrist and to assume a stalking attitude.

The following year I felt privileged when I was asked to join the Sotheby’s team working on the catalogue of the jewellery collection of the Duchess of Windsor, the wife of the former King Edward VIII. A team of specialists, cataloguers and researchers had to be assembled very quickly to work very fast in Geneva to comply with an extremely tight schedule. The result was a thoroughly researched and annotated catalogue that approached jewels as works of art and set the standard for the years to come. What a treat it was to open box after box of fabulous jewels created by Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels for the Duchess, a very homogeneous collection of the best produced by two maisons between the mid-1930s and the mid-1960s, combined with serious gemstones mounted by Harry Winston and whimsical creations by David Webb and Verdura. What a privilege to handle arguably the best ‘Great Cats’ ever created by Cartier and the spectacular invisibly set ‘feuilles de houx’ brooch by Van Cleef and Arpels. Hailed by couturiers and fashion writers as one of the world’s best dressed women, the Duchess used her Chanel, Schiaparelli, Mainbocher, Balenciaga and Givenchy dresses as a backdrop out of which her jewels stood out and could be admired. What the onlooker would not have been able to appreciate at the time is the fact that many of the jewels in the collection were inscribed with personal, intimate messages that punctuated the love story of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Reading those messages was intriguing and in many cases it helped to date the jewel with great accuracy, but it also made me feel slightly ill at ease as if I was intruding into the personal life of the Duke and Duchess.

The Duchess of Windsor's spectacular 'feuilles de houx' - or holly leaf brooch - created by Van Cleef & Arpels, Paris, 1936

Another determining moment in my progression of the appreciation of jewellery from different eras was the auction Jewels from The Princely Collection of Thurn und Taxis at Sotheby’s, Geneva, in 1992. The late Shirley Bury, who had been Keeper of the Metalwork Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum, was engaged to lead the cataloguing team. For several months I worked closely with Shirley who was meticulously accurate in her research and a perfectionist in her writing. It was a privilege to work alongside the V&A’s doyenne of 19th-century studies who revealed herself to be extremely generous with her knowledge and encouraged me to look at jewels of past eras with an inquisitive eye. The splendid, thoroughly researched catalogue was a tribute to one of the greatest and most diverse jewellery collections which I have ever come across ranging from the 18th century to the 1980s and including jewels as diverse as a Rajastan pearl, an emerald and diamond guluband and the magnificent pearl and diamond tiara created by Lemonnier in 1853 for the Empress Eugénie of the French, showing above and below.

Left: Princess Margarethe Klementine of Thurn und Taxis (1870-1955), pictured wearing the pearl and diamond tiara created by Lemonnier; in 1890 she wore the jewel on the occasion of her marriage to Albert, 8th Prince of Thurn und Taxis | Right: Empress Eugénie (1826-1920), for whom the tiara was originally created, depicted by Franz Xaver Winterhalter in 1853, the year of her marriage, to Napoleon III

Looking deep into what lies behind the sparkle of a jewel, researching its history, its provenance, the reason it was created, its relations with social history and the evolution of dress fashion therein continued to be – and still is – my interest and my driving force. This is why I am passionate about antique and vintage jewels.