Amsterdam was founded in the early 12th century, notably later than other European cities, as the challenging natural environment had stifled its development. In 1300 Amsterdam was awarded city rights, for commerce this meant freedom to hold markets, raise taxes and mint currency and for the individual, the right to travel and liberation from the rule of the feudal lord. In the late 16th century Amsterdam benefitted from the exodus of a sizeable proportion of Antwerp’s commercial and entrepreneurial classes seeking sanctuary from the conflicts ravaging the city. There is very little evidence of Amsterdam’s diamond industry prior to the 16th century, but it was certainly in existence. The marriage certificate of Willem Vermaet, dated 15 November 1586, lists his profession as diamond worker, and the document is often cited as evidence for the longevity of the business.

Amsterdam's magnificent diamond legacy | Part I

The skilled diamond workers of Amsterdam have been instrumental in the creation of some of the world’s most significant and important cut and polished diamonds.

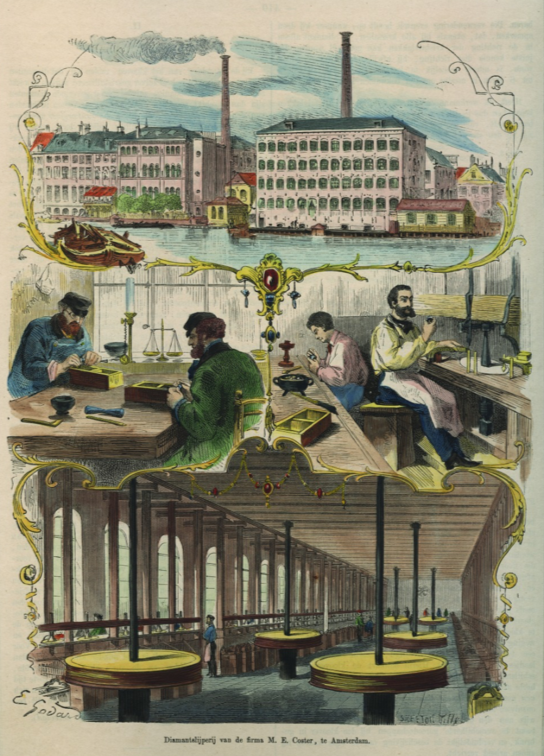

By 1750 it is estimated that around 600 families were making a good living working in the diamond industry, but even into the 1800s it was organised on a small scale with polishing mostly taking place in the home where women and children provided the manual power to drive the polishing machines. In the 1820s machines designed to be used in factories with the aid of horse power were introduced and in 1840 the first steam driven polishing facility was set up by the firm of Hont (founded in 1830), on Rapenburgerstraat, close to the River Amstel. In 1840 Moses Elias Coster established Coster Diamonds in a factory building on Waterlooplein, and five years later, the Diamond Polishers Association was founded – most of Amsterdam’s diamond merchants and jewellers joined – the Association also set up a fund to dispense aid and support orphans and widows.

From the 1850s Coster Diamonds worked on a number of remarkable, historic diamonds and held an almost unassailable position in the Amsterdam diamond industry.

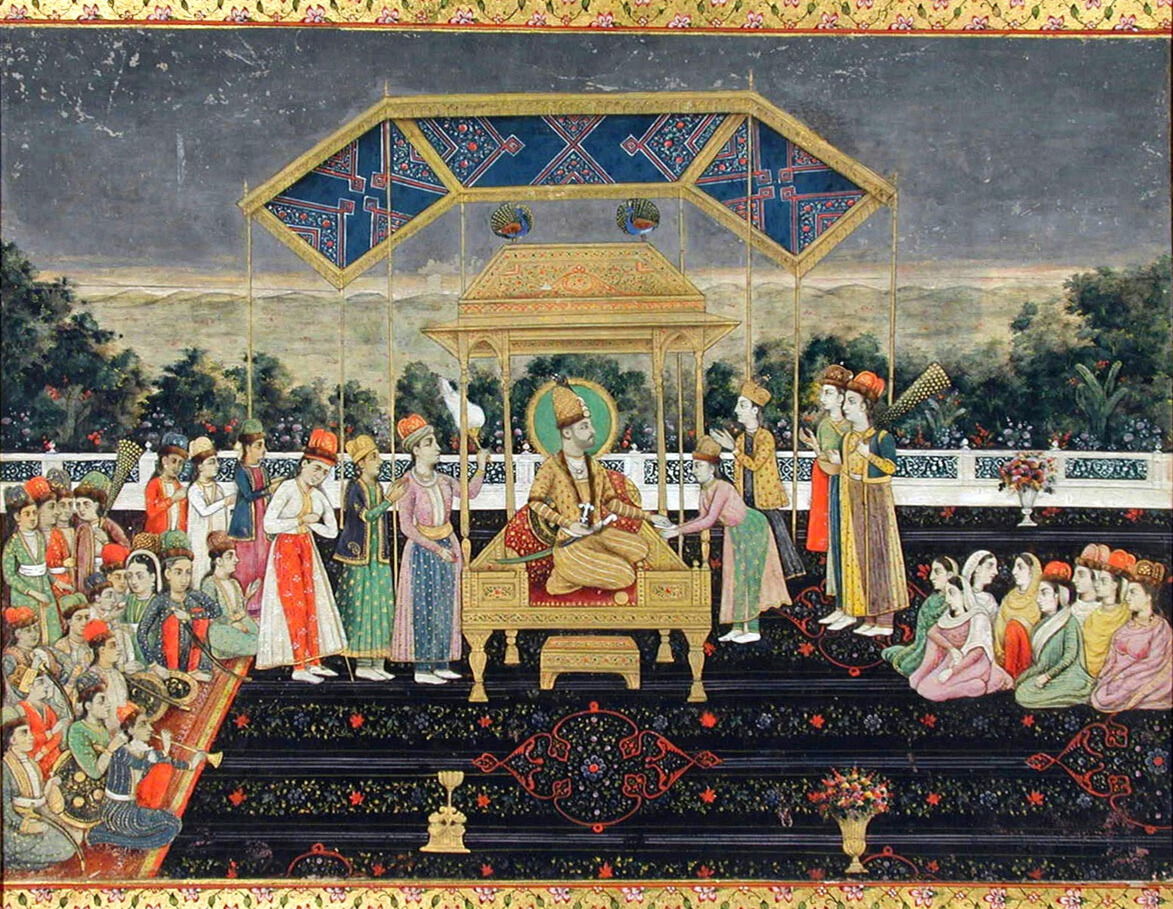

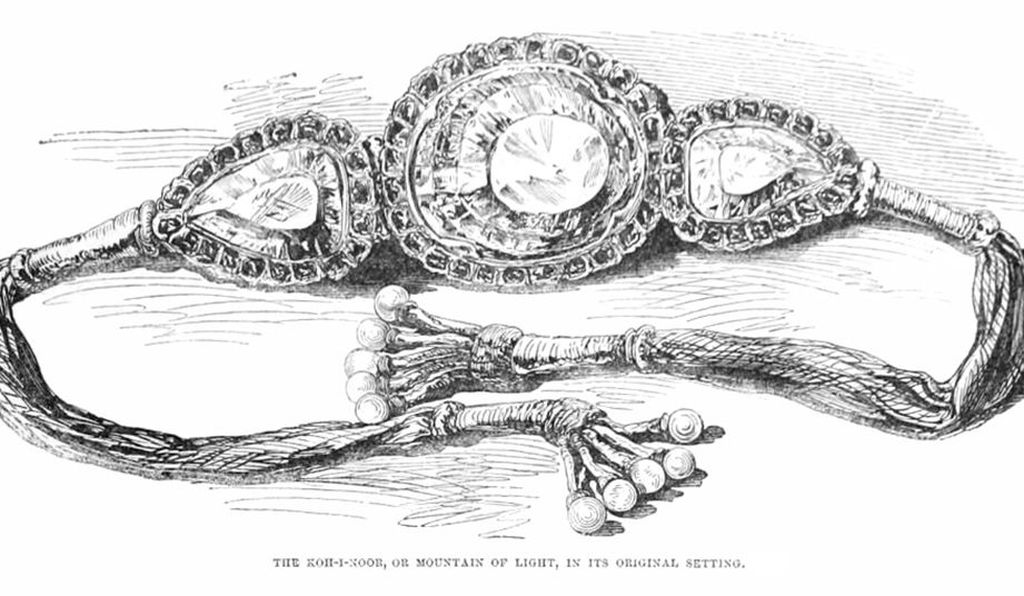

The first of these stones was the Koh-i-Noor, one of the world’s largest diamonds, found in India and with a colourful, hard to verify backstory prior to the 1740s. The Persian historian Muhammad Kazim Marvi in Tarikh-i ’alam-ara-yi Nadiri (The World-Illuminating History of Nader) relates that he saw the diamond embellishing the magnificent Peacock Throne, the royal seat created for the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in 1635. The Shah of Iran, Nader Shah (in power 1736-1747), took the throne as a war trophy and had it reassembled in his home country. The stone next passed into Afghan hands, then to the Sikh Empire, headed at the time by Ranjit Singh. In 1849 the East India Company took control of the Sikh Empire and with this came possession of the treasures stored in the Lahore Treasury. The Governor General of India, James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, (later Lord Dalhousie) had his sights on the Koh-i-Noor as an appropriate addition to the Crown Jewels of Queen Victoria. The Treaty of Lahore stated ‘…the gem called the Koh-i-Noor…shall be surrendered…to the Queen of England’. Dalhousie believed that Britain’s participation in two unnecessary wars justified Victoria’s acquisition of the stone, with its ‘…fitting resting place in the crown in Britain’.

The Koh-i-Noor was officially presented to the Queen at Buckingham Palace on 3 July 1850, by the Deputy Chairman of the East India Co., conveniently the year of the 250th anniversary of the Company’s founding. When compared with her European royal peers Queen Victoria did not own many important jewels, and the Koh-i-Noor would be a powerful symbol of her authority. The stone was exhibited in the Great Exhibition of 1851, but it was poorly received and in order to quash the negative reports it was moved to a small tent where six gas lights and twelve small mirrors were positioned to enhance its sparkle. The Times, on 16 June 1851, reported that ‘the result still remains unsatisfactory’, and after consulting with minerologists and having gained the permission of the government, Albert instructed Coster Diamonds to re-cut the stone.

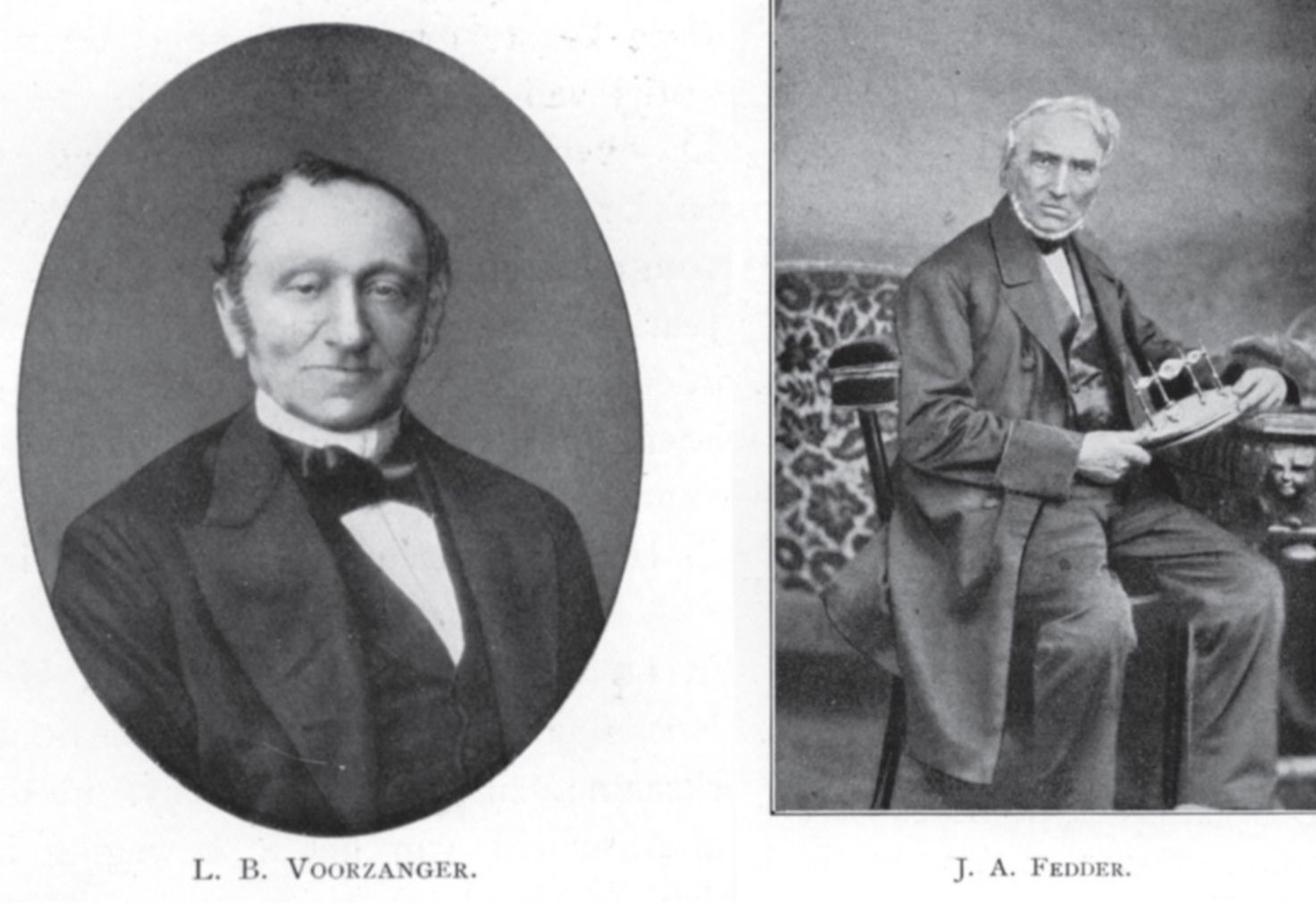

Two of Coster Diamonds’ most experienced workers, Levie Benjamin Voorzanger and J A Fedder, came to London in July 1852 and started work in the Panton Street premises of Garrard & Co. (the first Crown Jeweller appointed in 1843). A steam powered mill had been built specifically for the cutting, Prince Albert was present, along with James Tennant, the Queen’s mineralogist, and the Duke of Wellington, aged 83 and Britain’s most celebrated military leader, was given the honour of making the first cut. The cutting took 38 days, it cost Prince Albert £8,000 and the finished stone weighed 105.6 carats with 43% of its original weight lost. Voorzanger was credited with having removed one of the stone’s more problematic internal flaws, and although Albert was said to be troubled by its reduced size gemmologists agreed with Voorzanger’s methods and the outcome.

Queen Victoria wore the Koh-i-Noor in a number of different jewels, and after her death it was set in the new crown made for and worn by Queen Alexandra at the coronation of Edward VII in 1902. Queen Mary also wore a new crown featuring the Koh-i-Noor, created by Garrard, for George V’s coronation in 1911; the same crown was worn by Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) at the coronation of George VI in 1937 and the diamond was set as the central stone in the crown worn by the Queen Mother at the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953. In 2023 Queen Camilla wore a modified version of Queen Mary’s crown, but it did not include the Koh-i-Noor.